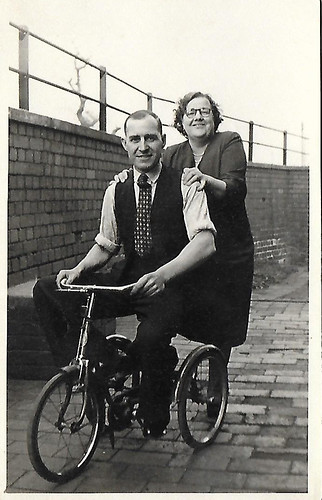

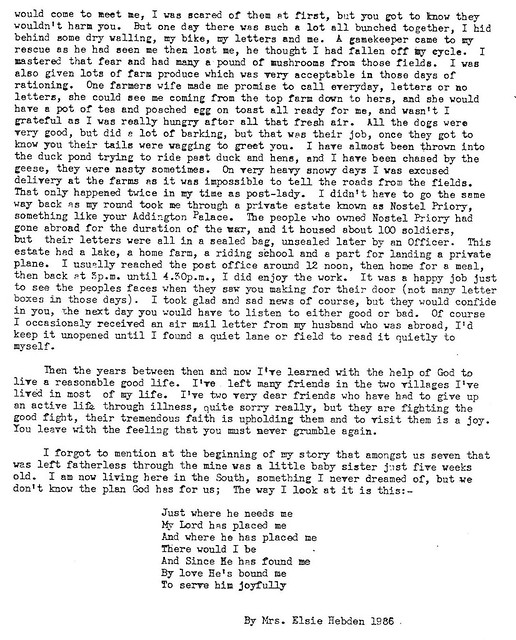

The following account was written by my Great Auntie, Elsie Hebden in 1986. In it she reflects of her life in Walton and Crofton. I was lucky to go to her house with my grandma when I was a kid. The photo above might seem unrelated to this story but that is her above on the right dressed as a man, next to her brother, my grandad – Albert Knowles, dressed as a woman. I don’t know the story behind the picture, it must have been a fancy dress party or something; they never dressed like that when I knew them! It does demonstrate the wonderful sense of fun that those growing up and living in our local mining communities often demonstrated. They lived tough and often difficult lives, but that did not mean they had to take themselves seriously.

While the family lived in Ings Cottages (“The Spike”) near Walton Pit, tragedy struck when their father died in a mining accident. Indeed, my grandad recalls seeing a body being brought from the mine but had at the time did not know that it was his own dad.

The following account is quite moving in parts, though that might be due to my personal family connection. It brings me back in a kind of spiritual contact with people that I once knew and loved. It also gives us all an insight into how people viewed their local area, how they lived their lives and the how they responded to the challenges that fate threw their way.

I will now leave Elsie to give you an insight into the world of her own past.

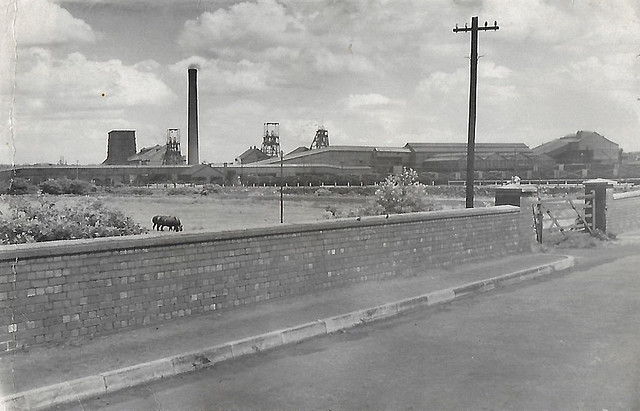

I was one of a family of seven, and lived in a mining village. The houses we lived in were quite close to the colliery. I should sway there would be about sixty-four houses.

We hadn’t much of this world’s goods, but we were healthy and happy, there were good times and bad, and even as children we knew well the dangers of that mine. We knew all about the accidents that happened almost daily, fathers, uncles, brothers, cousins and friends were brought up from underground minus limbs, blinded or even killed outright by heavy falls of rock or coal, or gas explosions. You will of course have heard how they took down a canary in a cage to test for gas after an explosion. If the canary wilted or died, then the place was unfit for men to work there for a while. They have only recently stopped making that test, it had been going on for a lot of years.

In all cases of death through the Mine, there would be a collection from house to house, but the money collected would not go on flowers, it would be given to the widows or orphans as the case may be. Everyone helped each other in that little community in sad times or glad times. One thing we had plenty of, and that was coal. It was free in those days, and still is I think to anyone who works at the Mine.

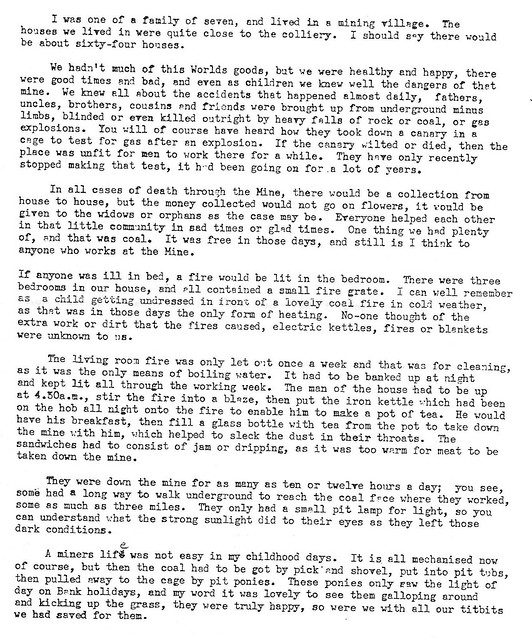

If anyone was ill in bed, a fire would be lit in the bedroom. There were three bedrooms in our house, and all contained a small fire grate. I can well remember as a child getting undress in front of a lovely coal fire in the cold weather, as that was in those days the only form of heating. No-one thought of the extra work or dirt that the fires caused, electric kettles, fires or blankets were unknown to us.

The living room fire was only let out once a week and that was for cleaning, as it was the only means of boiling water. It had to be banked up at night and kept lit all through the working week. The man of the house had to be up at 4.30a.m., stir the fire into a blaze, then put the iron kettle which had been on the hob all night onto the fire to enable him to make a pot of tea. I would have his breakfast, then fill a glass bottle with tea from the pot to take down the mine with him, which helped to sleck the dust in their throats. The sandwiches had to consist of jam or dripping, as it was too warm for meat to be taken down the mine.

They were down the mine for as many as ten or twelve hours a day; you see, some had a long way to walk underground to reach the coal face where they worked, some as much as three miles. They only had a small pit lamp for light, so you can understand what the strong sunlight did to their eyes as they left those dark conditions.

A miner’s life was not easy in my childhood days. It is all mechanised now of course, but then the coal had to be got by pick and shovel, put into the pit tubs, then pulled away to the cage by pit ponies. These ponies only saw the light of day on Bank holidays, and my word it was lovely to see them galloping around and kicking up the grass, they were truly happy, so were we with all our titbits we had saved for them.

Now, when I was twelve, my father was killed at work, the roof caved in. The men my father was working with had time to get clear. The rescue party quickly came, but my father was dead by the time they got to him. Now my mother who was 39 years old was allowed a widow’s pension of 10/- per week, a little from the colliery to help with the pension until we reached the age of fourteen and able to work, so to keep us tidy and well fed, she did sewing or papering for other people. She was a good living woman, and she saw that we all went to Sunday school in the next village. Our Sunday clothes were brushed and put away every Monday until the following Sunday. I am proud of my mother, it must have been a hard time for her. When I was fifteen, we left those houses and came to live in the village I have just left.

I helped mum until the age of seventeen, when I was sent into domestic service. I went to live in a doctor’s house in Wakefield about four miles away. The doctor and his family were not church people, so didn’t care where I went in my spare time. I tried several churches and chapels, but didn’t seem happy at any but my own. I was only allowed home every alternate Sunday, so one Sunday evening (Summer time of course), I made up my mind to find out what the town had to offer one, so I powdered and rouged my face with materials previously bought from the newly opened Woolworths store (remember nothing in these stores was over sixpence), something my mother would not have allowed, but I was thrown on my own resources and could so easily have gone on the downward path, but God thought otherwise or so it seems, because as I walked along hoping to find something better than church, I heard a band playing. Thinking it was in the park close by, I went that way but lost the sound, so turned around and went the opposite way and came upon a crowd of people. I pushed my way to the front, I have never seen or heard Salvationists before, or heard public speaking, but I did enjoy the songs, choruses and prayers, I even marched down to the Citadel with them.

The hall became my place of worship for the next four years, along with my own church in between, but I do say here and now that God led me that Sunday as I could easily have gone the opposite way. I thank Him and pray that the desire to serve him will remain with me all my earthly life.

In 1935 I married a young man I had known most of my life, then in four years’ time came the war. My husband joined the R. A. F. in 1940 and stayed in for the next five years. In my village at that time of 1940 if you had room you were expected to take in evacuee’s. I had a house with three bedrooms and just me at home. As they had just brought about 100 or so people from London to our village to be housed, a lady with two babies was brought to me, she came from Plaistow and was very sad a having to leave her home in London, but it was God who sent her to me, having these children and their mother, as I had just taken a job as post-lady, so we got on well together, her with her babies and me having someone to come home to at the end of my day’s work (we still write to each other).

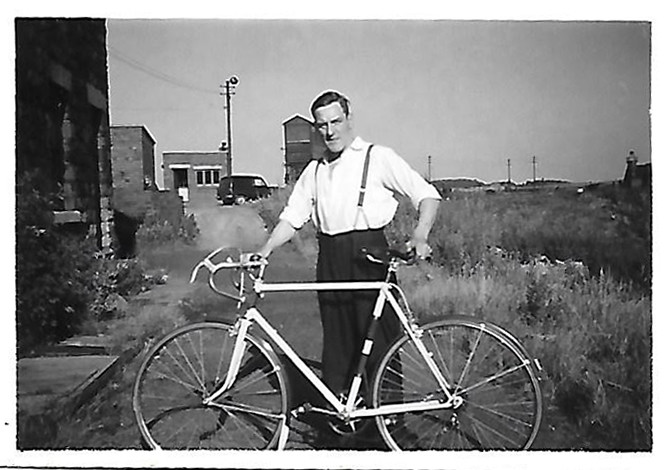

Now, to my job as post-lady I had to use a bicycle which I already possessed. I had to be at the post office at 6a.m., there were three of us sorting letters until 7.15a.m., then each of us off on our different routes. My job was less letters to distribute, but father to go. I loved the open air part of it. I had to face all weathers of course, my letters were for the outlying farms, colliery houses and lonely railway house, also amongst my letters was the daily paper which had to be posted as they didn’t have paper deliveries out there, so it meant going to most of the farms every day. I had quite a number of farms, sometimes as many as six fields between each, so it meant getting off my big, opening gates, even lifting my cycle over styles, and more over than not, cows would come to meet me, I was scared of them at first, but you got to know they wouldn’t harm you.

But one day there was such a lot all bunched together, I hid behind some dry walling, my bike, my letters and me. A gamekeeper came to my rescue as he had seen me then lost me, he thought I had fallen off my cycle. I mastered that fear and had many a pound of mushrooms from those fields. I was also given lots of farm produce which was very acceptable in those days of rationing. One farmer’s wife made me promise to call every day, letters or no letters, she could see me coming from the top farm down to hers, and she would have a pot of tea and poached eff on the toast all ready for me, and wasn’t I grateful as I was really hungry after all that fresh air.

All the dogs were very good, but did a lot of barking, but that was their job, once they got to know you their tails were wagging to greet you. I have almost been thrown into the duck pond trying to ride past duck and hens, and I have been chased by the geese, they were nasty sometimes.

On very heavy snowy days I was excused delivery at the farms as it was impossible to tell the roads from the fields. That only happened twice in my times as post-lady. I didn’t have to got the same way back as my round took me through a private estate known as Nostel Priory, something like your Addington Palace. The people who owned Nostel Priory had gone abroad for the duration of the war, and it housed about 100 soldiers, but their letters were all in a sealed bag, unsealed later by an Officer. This estate had a lake, a home farm, a riding school and a park for landing a private plane.

I usually reached the post office around 12 noon, then home for a meal, then back at 3p.m until 4.30p.m., I did enjoy the work. It was a happy job just to see people’s faces when they saw you making for their door (not many letter boxes in those days). I took glad and sad news of course, but they would confide in you, the next day you would have to listen to either good or bad. Of course I occasionally received an air mail letter from my husband who was abroad, I’d keep it unopened until I found a quiet lane or field to read it quietly to myself.

Then the years between then and now I’ve learned with the help of God to live a reasonable good life. I’ve left many friends in the two villages I’ve lived in most of my life. I’ve very two dear friends who have had to give up an active life through illness, quite sorry really, but they are fighting the good fight, their tremendous faith is upholding them and to visit them is a joy. You leave with the feeling that you must never grumble again.

I forgot to mention at the beginning of my story that amongst us seven that was left fatherless through the mine was a little baby sister just five weeks old. I am now living here in the South, something I never dreamed of, but we don’t know the plan God has for us; They way I look at it is this:-

Just where he needs me

My Lord has placed me

And where he has placed me

There would I be

And Since He has found me

By love He’s bound me

To serve him joyfully

By Mrs. Elsie Hebden 1986